When Memory is Traumatic: A Critical Study of

Bangla Autobiography Dandakaranyer

Dinguli

Jyoti Biswas

Ph. D. Research Scholar

Dept. of English Studies

Central University of Jharkhand

Jharkhand, India

Abstract:

Autobiography is a valuable repository of memory, both personal and

collective. It encompasses familial accounts of happiness and suffering; and at

the same time its narrative remains a faithful representation of a whole

community. Besides, it covers up social and political timeline as well. In this

respect, an autobiography is not simply a family saga; rather its narrative

accounts for understanding contemporary social situations. To contextualize it,

political cataclysm of Partition of Bengal into East Pakistan and West Bengal

in 1947 creates an identity crisis among its victims, that the victimhood leads

to formation of traumatic memory. Dandakāranyer

Dinguli (Days of Dandakāranya), a Bangla autobiography written by Sudhir

Ranjan Haldar is a valuable repository of traumatic memory that both records

the personal recollections and social commentary. The present paper focuses

primarily on theoretical dimension of traumatic memory; and examines two

important issues in the selected text: traumatic memory of Namo community being

refugee in India; and traumatic memory of Namo community within a vicious

circle of caste-based discrimination in their refugee life in refugee

camps. An individual’s personal

narrative by the virtue of its representational dimension becomes a collective

utterance for entire community; it brings out a common ethnic identity and

commonly felt ethnic trauma running through the individual author and other

community members in an unmistakable manner.

Keywords: partition;

trauma; memory; refugee; caste discrimination; autobiography

There is no life without trauma. There is no

history without trauma. Some lives will forever be overshadowed by violent

histories, including colonial invasions, slavery, totalitarianism,

dictatorships, wars, and genocide…Trauma…violently halts the flow of time,

fractures the self, and punctuates memory and language.

―Gabriele Schwab1

Memory and trauma seem to have an inseparable communion in human

survival. Memories or storage of past incidents in human brain bear varied

contexts in which they take place. Some contexts are familial, some

professional, and some contexts social or political. Each context develops its

structural framework for creating respective memory narrative. In other words,

childhood memory of happiness in familial context is quite different from

traumatic memory of casteist/racist discrimination in professional context. The

narrative of memory recollection whether oral or verbal is, therefore, seen

bound with contextual impact. Modern-day Jews feel it unbearable to hark back

the cursed days of the Holocaust, that global Jews community live with the

traumatic memory of Nazi operation till date. Although utterly painful and

heart-wrenching, memory of lost homeland to millions of Namo2

community in the Partition is inseparable. Speaking especially of Namo

community members, they being the worst victims of partition have still been

suffering from an identity crisis even after more than seventy years as NRC3

has evoked it afresh since 2014. The

entire trajectory of the Partition and its deadly aftermath has given rise to

what can be termed as ‘traumatic memory’ among the community members, both first

generation victims and successive generations. Memory stained with trauma, or traumatic memory therefore has become an

essential psychic component in their reminiscence of the past. The selected

text Dandakāranyer Dinguli (Days of

Dandakaranya), by Sudhir Ranjan Haldar, a member of Namo community, who along

with thousands of fellow community members migrated in the aftermath of the

Partition from erstwhile East Bengal-turned-East Pakistan to Dandakaranya,

India in 1965, narrates the traumatic memory of his life and simultaneously of

his victimized community in his autobiography in quintessential manner.

OED defines trauma as a

“psychic injury, esp. one caused by emotional shock the memory of which is

repressed and remains unhealed; an internal injury, esp. to the brain, which

may result in a behavioural disorder of organic origin” (441). OED records

early commentary of trauma by some of the prominent practitioners of psychology

such as William James who says that trauma denotes “certain reminiscences of

the shock fall into the subliminal consciousness where they can only be

discovered in ‘hypnoid’ state” (441). Henderson and Gillespie’s Textbook of Psychiatry for Students and

Practitioners (1969) puts the following definition of trauma that it is a

“mental symptoms in one of the two ways. Either it causes structural injury to

the brain, or it causes emotional disturbances” (qtd. in OED 441). On the other hand, OED defines memory in

multiple ways, such as “the faculty by which things are remembered; capacity

for retaining, perpetuating, or reviving the thought of things past”; or “The

recollection (of something) perpetuated amongst people; what is remembered of a

person, object or event”; or “The length of time over which the recollection of

a person or a number of persons extends” (596-98). To analyze aforementioned

definitions of both trauma and memory, it can be deducted that ‘traumatic

memory’ is primarily the recollection of traumatic experiences either by an

individual or by a group the manifestation of which can be found through oral

and verbal narratives, although other mediums of cognitive ability, such as

archaeological evidence, photography, documentary, oral archive also help us

develop the narrative of loss of cultural past.

Psychic trauma as a psychological property of

human consciousness has been a subject of research and investigation to

psychologists and clinical practitioners for over a century. Pioneered by

British surgeon Sir John Eric Erichsen (1818-1896) who studied trauma as a

disease of mind, one of the early psychological formations of psychic trauma is

developed in Breuer-Freud cathartic method4 that was based on

hysteria in which reminiscences occupy a crucial role. According to Ruth Leys,

the early psychological study of trauma is predominantly underlined as

“wounding of the mind brought about by sudden, unexpected, emotional shock. The

emphasis began to fall on the hysterical shattering of the personality

consequent on a situation of extreme terror of fright” (4). Although psychological

investigation and research on hysteria and other sorts of mental depression

have long been recognized by practitioners as vital resources to study

traumatic memory in individual self, treatment and research of trauma outside

psychology has been pioneered by many cultural theorists and historians, such

as Cathy Caruth, Dominic LaCapra, Elain Scarry, Marita Sturken, E. Ann Kalpan,

and Ruth Ley. Seminal texts, such as Unclaimed

Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History (1995), History and Memory after Auschwitz (2001) and Trauma Culture: The Politics of Terror and Loss in the Media and

Literature (2005) have paved the way for research of trauma and memory in

Humanities. Maurice Stevens explicates how trauma turns into a cultural essence

in human life: “At its base is the notion that trauma is not simply a concept

that describes particularly overwhelming events…but is a cultural object whose

function produces particular types of objects, an predisposes specific affect

flows that it then manages and ultimately shunts into political projects of

various types” (20). The function of trauma as a cultural object shifts our

attention from purely being a psychological disease, almost hysteric to lived

experiences of either an individual or an entire community, the experiences

which consequently turn the shape into both oral and verbal narrative. These

narratives provide readers with what Maurice Stevens calls critical trauma

studies (Stevens 25).

According to Gabriele Schwab trauma “is

concerned with what happens to psychic life in the wake of unbearable violence

and focuses on irresolvable…loses that occurred under catastrophic

circumstances that bring us to the abyss of human abjection” (3). In this

respect, recollections and remembrances of the victims who suffer from all

sorts of catastrophe and violence become the primary sources to studying the

construction of traumatic memory that usually turns into a cultural property in

the sense that narrative of such memories got transmitted from source

generation to next generations. This trans-generational transmission of

traumatic experiences of first generation is inherited by the successive

generations in the form of oral narrative or verbal narrative. The way

grandparents and other elders of a family narrate folktale to young boys and

girls, memory sharing takes the similar sort of transmission. In this respect,

trauma becomes the content and memory the form of entire narrative structure.

These narratives have tended “to focus on the trauma and related…memories of victims

and victimized people” (Schwab 22).

It has to be noted that an individual

traumatic memory very often becomes representative oral or verbal narrative for

an entire community. An individual self does not grow in isolation. She/he

grows up in a family and in a large community. Throughout this growth right

from childhood she/he learns language and family culture. Following the same

imitative process her/his mental growth is traceable in constant interaction

with others because it is through imitation of other family members as well as

community members the individual’s psychic growth keeps the sense impressions

in the mind. Maurice Halbwachs (1877-1945), a noted sociologist who pioneered

the study of mémoire collective or

collective memory observes on individual memory that “individual recollections

[are] those recollections in which every individual retrieves his own past, and

often thinks that this is all that he can retrieve…each family member

recollects in his own manner the common familial past” (54). Although Halbwachs

puts much emphasis on the collective matrix of familial memory (61), he

considers that family constitutes “the essential social unity” (64). Looking

beyond family matrix, the germination of collective memory that germinates in

the family stretches its expansion beyond the family. An individual’s constant

interaction with the society brings forth a new dimension in the formation of

an individual’s personal recollections of past, i.e. it gets merged with

recollections of same cultural, social and political phenomena taken place in

this society, that can be called collective memory.

Traumatic memory with oral and verbal

narrative is an essential resource to scholars of Humanities to study the

history of cataclysm that resulted in such mental wound; it also occupies a

crucial place in formulating cultural identity among respective members of the

victimized group. As already discussed that autobiographical recollection of

past is personal as well as collective in respective contemporary socio-political

history and community-oriented identity formation, autobiography as written

document is the closest and most authentic record to study the making of

traumatic memory both personal and collective, to interrogate and then to

explicate the respective socio-political context in which the people become

victims, and to assess the text’s

cultural importance among its people and at the same time among general

readers. The present paper now discusses the selected text, the historical

context and textual/thematic analysis of selected excerpts to justify traumatic

memory as the central theme of the text.

The primary text Dandakaranyer Dinguli (Days of Dandakaranya) is a Bangla autobiography written by Sudhir Ranjan

Haldar, first published in 2014. Haldar was born in 1946 in village Moishani of

Barishal district in erstwhile East Bengal that became East Pakistan after the

Partition of British India into Secular India and Muslim Pakistan. Born in a

Namo community, Haldar qualified Secondary School certificate from Sekherhat

High School in 1963 in erstwhile East Pakistan. While studying Science at local

College, he witnessed raging flame of communal riots between majority Muslims

and minority non-Muslims5 including Namo community in adjacent

villages and in other districts throughout East Pakistan. Along with many

others, Haldar migrated to West Bengal, India in 1964. After a temporary

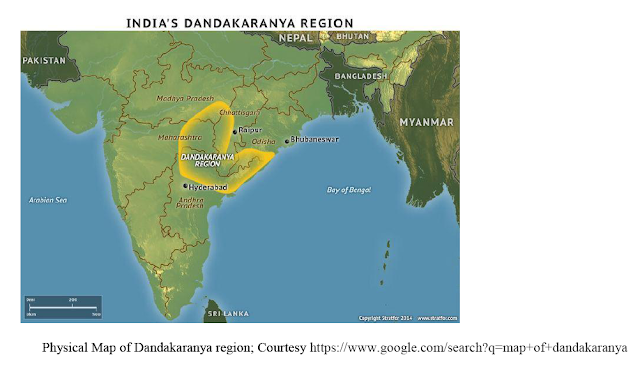

settlement there, he migrated to Dandakaranya. Dandakaranya6 is a

physiographic barren, hilly region in east-central India. Its landmass

comprises of almost 35,600 square miles. It spans about 200 miles from north to

south and 300 miles from east to west.

It is consisted of some parts of Chattisgarh, Odisha, Telengana and

Andhra Pradesh, an intersection of lands taken from different adjacent states.

Its longitudinal and latitudinal measurements are 82°05¢00²E and

19°05¢00²N respectively. It is located in such

intersection because it has been created so for specific purpose.

The history of Dandakaranya goes back to

refugee resettlement in 1958 and for soil conservation in 1947. Thinly

populated by some indigenous Tribes, Indian government arranged this

intersectional location for resettlement of thousands of refugees who started

pouring into West Bengal and other Indian states from erstwhile East Pakistan

right after the Partition. The refugee resettlement in Dandakaranya has taken

place in different phases. The first phase began from 1947 and the second phase

from 1971. Throughout these phases, migration and resettlement of thousands of

Namo community people formed the background of this autobiography.

In the autobiographical writings of Namo

writers there are two broad socio-political themes dealt with: social

marginalization in the caste-based hierarchical system in Bengal; and politics

of the Partition and their victimhood. Despite the fact that research and

publications on the Partition historiography have been continuing

over a long period of time, the questions respective Namo community writers and

scholars raise remain neglected in the popular Partition historiography. The

binary of Hindu-Muslim seems to be too dominant to let other enquiries creep

into the intellectual space. The three central questions raised by Namo

writers, scholars and historians are: 1. Despite the fact that Muslims and

Hindus divided their respective landmass for themselves in the name of East Pakistan

and West Bengal in 1947, why were Namo-populated districts of Faridpur, Khulna,

Jessore, Barishal kept outside Hindu-majority West Bengal? 2. What are the

reasons that only Namo community refugees were sent to Dandakaranya, Andaman

and Nicobar Islands and other far-off places in refugee resettlement programs

in different phases after 1947 and after 1971? 3. Why were only Namo community

members massacred in deadly Marichjhanpi by Brahminical Communist government of

West Bengal in 1978-79?7 The present text not only narrates the

lived experiences of the author and other fellow members, but also raises these

three issues and provides us a clue to understand the politics of caste-based

hierarchy even in the Partition and in refugee distribution and resettlement

programs thereafter. A cluster of Namo scholars and historians, such as Dr.

Oneil R. Biswas, Dr. Upendranath Biswas, Dr. Gyanprakash Mandal, Dr. Atul K.

Biswas, Mr. Swapan Kumar Biswas, Dr. Sunil Kumar Roy, Dr. Manoshanta Biswas;

and writers, such as Kapil K. Thakur, Manohar M. Biswas, Jatin Bala, Nakul

Mallik, Jagatbandhu Biswas, Kalyani C. Thakur and others have done a

considerable research on Partition and its aftermath. Dr. Manoshanta Biswas

argues:

Independence and the Bengal partition in 1947

were not quite a favorable phenomenon to many marginalized communities, such as

Rajbanshi and Namasudra. The Bengal partition in 1947 weakened the impact of

independently-built political movements of both communities and at the same

time divided their political ideology and consensus by dividing the population

into two lands. “Transfer of power” was carried out based on the communal

demand of Hindus and Muslims. The religious-political demand of the

marginalized communities was beyond the calculation. (my trans.; 262)

Autobiographies written by Namo writers, such

as Dandakaronyer Dinguli (Days

of Dandakaranya) by Sudhir Ranjan

Haldar; Smritir Pata Theke (From the

Leaves of Memory) by Jagatbandhu Biswas; Amar

Bhubone Ami Benche Thaki (Surviving in My World) by Manohar M. Biswas; Shikor Chhenra Jibon (Uprooted Life) by

Jatin Bala and others interrogate all these questions and to a great extant

critique the caste-based hierarchy that was initiated behind the Partition. All

these autobiographical writings highlight two interrelated themes: traumatic memory

emerged out of their refugee life; and traumatic memory emerged out of

caste-based discrimination in refugee camps. Dandakaranyer Dinguli adds another dimension, i.e. it depicts the

refugee life of thousands of Namo community people in Dandakaranya that is a

far-off land from West Bengal. The readers come to know that not only in

different refugee camps and colonies in West Bengal, but also in Dandakaranya

too, Namo refugees became the victims of dual marginalization in which

caste-based discrimination played a crucial role.

The text Dandakaranyer

Dinguli is a literary product of the author’s superannuated life, hence

overloaded with reflective strain of words and expressions that are too

emotional and that influence its readers by travelling back to 1950s and 60s to

visualize the mass exodus crossing the border of East Pakistan and pouring into

an imaginary flux known as West Bengal with a blazing hope that it would be

their destination, no matter how illusory their hope would be. The images or

photographs of mass exodus of refugees to West Bengal through Gede border or

Petropole8 border kept in West Bengal State Archives or made

available in Google homogenize the author’s verbal presentation of refugee

life. Sudhir Ranjan Haldar begins his autobiography with not only with an acute

feeling of homesickness, but also with a possible anticipation of illusion of

future life:

With the turbulence in my mind that bulged up

on the eve of forsaking my birthplace, I set off onto my marathon long ago;

this is almost forty years that I am still sprinting on the circular court of

my life’s marathon. The turbulence has not been weakened yet, nor terminated my

sprinting. I really don’t know how long I have to run to reach to my

destination.

Following

the unstoppable sprinting, I reached Dandakaranya as if a floating water

hyacinth; it was that place where I have seen millions of refugees floating in

and getting ashore―all of them were the innocent victims the Partition. (my

trans.; 7)

The memory of bygone days has taken the shape

of a verbal narrative that is charged with a feeling of anguish and regret.

That sort of beginning of an autobiography has provided a hint to readers that

right from the beginning the author writes on behalf of an entire victimized

community that got displaced from their homeland in the Partition of Bengal. On

the other hand, it sets the tone for rest of the text that will keep readers

well-grounded on the thematic treatment. The factual details the author puts

along with authentic narrative of refugee resettlement is also helpful to

locate the time and place of the entire narrative. It bears its historical

authenticity as well by eliminating fictitious narrative.

The author explains the background why

thousands of minority non-Muslims fled East Pakistan in 1950s and 60s. It

primarily focuses on two interrelated situations: religious and political.

Since East Pakistan was Muslim-majority, the Islamic Law for non-believers

(known as Kafir) justifies the increasing incidents of rape, molestation on

non-Muslim women, mass killing and loot on non-Muslim settlements in the name

of holy Jihad. On the other hand, political instigation by Urdu-speaking West

Pakistani government in Lahore worsened the minority crisis even more intensely.

The author gives us the following account of Islamic atrocities on minority

non-Muslims in the following way:

There was a great humdrum going on in East

Pakistan at that time. At the beginning of the year a deadly riot took place

around our locality. Killing, loot, rape, setting houses on fire―they chose

only Hindus, Buddhists, and other non-Muslims and relentless torture was

carried out almost with the support of the government. Many non-Muslims already

fled from East Pakistan to save the dignity of their women and their life at

large. (my trans.; 8)

Two issues, i.e. the dignity and respect of

non-Muslim women and the safety of non-Muslim communities in general were their

major preoccupation. The mental tension of a father for his young daughter or

of a young man for his newly-married wife, or a mother’s deep concern for her

young son or a young wife’s mental unrest for her husband in such terrorized,

religiously and politically hostile environment became inseparable part of

their daily living. It shows how traumatic their living was during the initial

decades followed by the Partition. Their memory was submerged by the unbearable

weight of terror and trauma.

As it was mandated in the religious

bifurcation that Pakistan with its West and East provinces was a political

entity for Muslims, the mind of minority non-Muslims was naturally and

desperately craved for India, especially West Bengal that was supposed to be

the final destination. In this part of the text, especially the episodes of

communal riots and political provocations highlight authentically how

inhospitable the native land turned and how insecure thousands of non-Muslims,

especially Namo community members were. It remains the background of their

forced migration to West Bengal in 1950s and 60s. It has to be noted that Namo

community is traditionally agrarian, having inseparable link with the soil. Dr.

Manoshanta Biswas’s research shows how difficult it was for them to terminate

their traditional livelihood and migrate to West Bengal overnight. On the

contrary, only upper castes who were politically and financially privileged

managed to settle to West Bengal before the burning flame of communal riot

could affect them badly (265-66).

The text focuses next on the narrative of

refugee life that in many ways multiplied their trauma and identity crisis. In

other words, if religious terror changed their peaceful living in their

motherland into unbearable trauma and extreme form of insecurity, their refugee

life in West Bengal and later on in Dandakaranya exposed them harshly in the

refugee camps. The text documents this new phase of their life authentically

and visually. The episode of Dandakaranya begins with a mythical account of

this place that this place was the famous forest in which prince Rama, his wife

Sita and his brother Laxmana spent their exile as it was narrated in Sanskrit

epic the Ramayana (30). As already

mentioned, this place was peopled by a few Tribes who might have been described

as demons in the epic. The author’s first encounter with this new place and its

inhabitants was of strange feeling because a man born and brought up in fertile

land of East Bengal or East Pakistan found quite difficult to cope with his new

environment and new language. Unlike many other Namo refugees who have been

resettled in different parts of West Bengal, the Namo people documented in this

text found for themselves a barren, forest land with unknown people and

language, as if a fish out of the water. His first arrival was at Ambagura by

bus. After staying a few days there, he headed toward Malkangiri. At

Malkangiri, he found around himself the typical hill and forest for which

Dandakaranya was well-known. There he encountered first what was like being a

marginalized despite being refugee along with others. He searched for a hotel

for temporary shelter. When he contacted the officials at Dandakaranya Project

office headquarter, he met with one Kalidas Som, a clerk in the office. The

office clerk arranged for him a temporary shelter before he finally shifted to

new Tribal village as an appointed teacher. One day, he and Kalidas Som were

talking about the prospect of new schools and education policy. On hearing that

the author would be appointed as a teacher in one primary school in a nearby

village, Kalidas Som expressed his concern: “How do you stay over there as a

teacher? You know this place was occupied mostly by all uncivilized castes,

such as Namo, Pod, Jele, Malo9 among others―all of them are

Scheduled Castes, all quite dirty and uncultured. Do you know how many teachers

already fled from these places?” (my trans.; 32-33). This observation of

Kalidas Som who indirectly hailed him as belonging to higher than those

Scheduled Castes who are traditionally considered as ‘Untouchables’ by Brahmins

and other Twice-born castes in Hindu society was the very first incident where

caste became a determinant factor for judging the social status of any

particular community. This observation by Kalidas Som was the first such

incident the author witnessed at Dandakaranya that the thousands of refugees

despite being homeless, utterly helpless in a foreign land couldn’t get any

respite from caste-based social hierarchy, a system that puts some castes

higher and some castes lower. The very first caste phenomenon in the refugee

settlements add a new dimension to this autobiography that caste-based

hierarchy is inseparable no matter how helpless and hopeless people might be in

any situation.

There are many such passages with reference

to caste status of the refugees. In another incident the author witnessed how

some castes, like Brahmins, Kayasthas hated Namo and other marginalized castes.

A fellow teacher, Shyamsundar Paul while talking about the refugee settlements

told the author: “What will happen if students don’t turn up in your school?

All refugees settled here are Scheduled Castes, all are uncivilized,

uneducated. Caste Hindus haven’t come here as a refugee that education will be

valued. All refugees belong to Namo, Pod, Jele, Malo and other castes” (my

trans.; 42). This episode gets extended to more than four pages and throughout

the narrative. What unmistakable here is the names of different castes into

which refugees are divided, such as

Brahmin, Kayastha, Namo, Pod, Jele, Malo. What is more evidential is the social

hierarchy. Namo, Pod, Jele, Malo and other castes which constitute majority of

refugees in different camps throughout Dandakaranya have been assigned a low

status. Being refugee is not enough; what is added with this fate is ‘lower

caste refugee.’

In his Annihilation

of Caste (1936), Dr. Ambedkar explains that despite the fact that division

of labor is found in every civilized society, the Hindu society has elevated it

onto division of laborers the categorization of which is based on caste-based

identity (263). Such insightful commentary helps us see that underlying dual

structures in all professional spaces in India. The text suggests that Kalidas

Som, Shyamsundar Paul and author Sudhir Ranjan Haldar were refugees. But as the

caste-based hierarchy is exposed, the author and his thousands of fellow Namo

community members were not only refugee, but to a great extent ‘lower caste

refugee.’ The concept of double marginalization in which Namo, Pod, Jele, Malo

castes suffered in refugee camps add a new dimension of such autobiography. Dandakaranyer Dinguli is an important

social document in another respect. It gives us an authentic description of

Marichjhanpi10 massacre carried out shamelessly by the Communist

government of West Bengal in 1978-79. Throughout a large section of the text,

the author provides us how Communist leaders, such Samar Mukherji, Jyoti Basu

frequently visited refugee camps in Dandakaranya and convinced them if

Communists would form political power in West Bengal, they would arrange

resettlement for them at Sundarban (133-34). There was a time when

thousands of Namo refugees migrated to Dandakaranya from West Bengal at the

initial period of refugee settlement programs. In 1977, the Communist

government came to power in West Bengal. Consequently the refugees in

Dandakaranya under the leadership of Satish Chandra Mandal asked the Communist

government to fulfill their promises. The author narrates another great episode

of mass exodus, this time from Dandakaranya to West Bengal: “Right from the beginning

of the year 1978, thousands of refugees started returning to West Bengal. More

the time was passing away more number of refugees were vacating different camps

of Dandakaranya. About seventy percent of refugee population already vacated

Dandakaranya by the end of that year” (my trans.; 134). They were resettled

first at Hansnabad camp before they were deported to Marichjhanpi. Refugee

camps at Hansnabad turned into unhygienic as the government refused to help

them with basic amenities. The author writes: “I have personally seen the

helplessness of thousands of refugees who are heading towards Marichjhanpi.

Since there was some transport problem in making their way to Marichjhanpi, the

refugees first settled at Hansnabad camps. They settled along two sides of the

railway track, in bushes, in jungles wherever they managed” (my trans.;

134-35). Rest of the incidents has become stained with blood of thousands of

innocent people who had fallen victims in the hand of Communist government. It

is known in history as the ‘Marichjhanpi Massacre of 1978-79’ in which only

Namo refugees were terribly victimized. The author gives us a ground report of

the barbarous act of rape, murder and butchery inflicted upon thousands of Namo

refugees who were asked by the government to settle to Marichjhanpi from

Dandakaranya:

They set up schools, constructed roads,

markets under the guide of Udbastu

Unnoinshil Samiti (Refugee Development Association) at Marichjhanpi. They

started business by setting up small scale industries, as if they created their

own new world. With their tireless effort they made large fishing pond, tobacco

factory, biscuit factory. Had they got government’s support they would have

flourished there at Marichjhanpi. But instead of helping them out, the Communist

government with their police and cadre raped women, looted their resources, set

their houses on fire, killed them mercilessly, massacred women and children and

in this way drove them away from Marichjhanpi again. (my trans.; 135)

The autobiography Dandakaranyer Dinguli contextualizes the Partition of undivided

Bengal in 1947, connects the political conspiracies intended to marginalize

Namo and other populous communities in the partition, documents the deadly

aftermath in the form of rape, loot, mass killing, forced displacement of

thousands of Namo community members, exposes the political eloquence of Hindu

identity, and describe the plights and suffering of thousands of refugees who

have been deported to Dandakaranya. Throughout this tumultuous dimension, the

autobiographical narrative of Sudhir Ranjan Haldar justifies conceptual

implication of double marginalization of Namo community refugees: one, their

identity being refugee; and second, their identity being ‘lower caste refugee.’

This double marginalization multiplies their traumatic memory that got

transmitted through generations. Dandakaranyer

Dinguli is one of the few texts that weave the very complicated and

delicate ‘traumatic narrative’ of a community’s victimhood in the historic

context of the Partition of their beloved East Bengal.

End Notes

1.

Gabriele Schwab is a noted

literary scholar, focusing on Holocaust and trauma in her writings. See Schwab,

Gabriele. Haunting Legacies: Violent

Histories and Transgenerational Trauma. New York, Columbia UP, 2010, P.42.

2.

In this paper instead of

using Namasudra, Namo is used to refer to this community. The original argument

behind this is, a cluster of scholars and activists of this community do

believe that a great political conspiracy was played by Brahmins to influence

the British government to introduce a new combined word Nama+Sudra in 1911

census to forcibly include a non-Aryan, non-Hindu ethnic group within the Hindu

fold. Now-a-days, many scholars and activists of this community introduce

themselves as ‘Namo.’ They do not acknowledge Namasudra. See Roy, Sunil Kumar. Itihase Namojati. Kolkata, Lalmati

Prokashon, 2019. Biswas, S. K. Untouchable

Chandals of India: The Democratic Movement. New Delhi, Gyan Publishing

House, 2013. Roy, Sunil Kumar. Nirbachito

Probondho Sonkolon. Kolkata, Janomon, 2015.

3. National Register of Citizens is a

legislative Act of registering all Indian citizens by Indian government. First

constituted in Citizenship Amendment Act, 1955 and amended later in 2003. It

has been implemented in Assam in 2013-14 and in 2019-20 by Government of India.

4.

Breuer-Freud cathartic

method is a psychoanalytic study on hysteria. Joseph Breuer’s famous case of

Anna O. was seminal for the study and development of Psychoanalysis. See

Breuer, Joseph and Sigmund Freud. Studies

in Hysteria. Translated by Nicola Luckhurst, London, Penguin Books,

2004.

5. In this paper, non-Muslims are referred to

those who do not follow Islam, such as Matuas, Buddhists, Christians, Sikhs,

Jains and Hindus. In India there is a peculiar tendency among general scholars

to categorize someone as Hindu if she/he is not a Muslim by faith. In the name

of Hinduism, many non-Hindu groups of people have been forcibly registered as

Hindu. In specific case, Namo people are not Hindus. In this respect, see

Biswas, Manoshanta. Banglar Matua

Amdolon: Somaj, Sanskriti, Rajniti. Kolkata, Setu Prokashani, 2016.

6. The refugee rehabilitation program was a key

political issue to the then Congress government. Since thousands of refugees

were pouring into West Bengal from erstwhile East Pakistan, Dandakaranya was

prepared to resettle refugees as well. See Elahi, K. Maudood. “Refugees in

Dandakaranya.” The International

Migration Review, vol. 15, no. ½, 1981, pp. 219-225. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2545338. Accessed 13

June 2021.

7. SojaKotha magazine edited by Harashit Sarkar has

brought out a special issue on Bengal Partition, Summer, 2020. Many Namo

scholars and writers have contributed in this issue. Mr. S. K. Biswas, Nakul

Mallik, Mrs. Madhabi Karmakar, Mr. Dilip Gayen, Mr. Dulal Krishna Biswas, Mr.

Mihir Sarkar, Mr. Jyoti Biswas have interpreted the Bengal Partition from a new

perspective in which Brahminical caste system and the political conspiracy have

been explained. See SojaKotha, Bangla-Bhag Special Issue, edited by

Harashit Sarkar, 5th year, vol. 1, 2020.

8. Two international gateways in West Bengal

connecting inter-border passage to Bangladesh. Since 1947 these gateways have

been common entrance point to refugees to come to West Bengal, India.

9. Names of some castes that have been marginalized

by Brahminical caste system in Bengal.

10.

Marichjhanpi is an island

situated in the mangrove forest of Sundarbans, in the district of South 24

Pargana, West Bengal. It is located at 22°06′25″N 88°57′04″E. It has an average elevation of 6 miters

(20ft.). It is approximately seventy-five kilometers away from Kolkata. The Communist government of West Bengal under the leadership of Jyoti

Basu invited thousands of Namo refugees

from Dandakaranya to settle at Marichjhanpi in 1978-79. It was followed by what

is known as Marichjhanpi Massacre. Jagadish Chandra Mandal has done an

authentic research work on it. See Mandal, Jagadish Chandra. Marichjhanpi: Noishobder Ontorale. 3rd

ed., Kolkata, People’s Book Society, 2018. To study the Marichjhanpi massacre

through poetic representation, see Biswas, Jyoti and Madhabi Karmakar. “Portrait of the Massacre: Two Dalit Poems on

Marichjhampi.” Perspectives on Indian Dalit Literature: Critical Responses,

edited by Dipak Giri, Bilaspur, Bookclinic Publishing, 2020, pp. 142-156.

Works Cited

Simpson, J. A., and E. S. C. Weiner, editors.

Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd

ed., vol. 18, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1989, p. 441.

ibid.

ibid.

---. Oxford

English Dictionary. 2nd ed., vol. 9, Oxford, Clarendon Press,

1989, pp. 596-98.

Leys, Ruth. Trauma: A Genealogy.

Chicago and London, Chicago UP, 2010, p. 4.

Stevens, Maurice. “Trauma Is as trauma Does:

The Politics of Affect in Catastrophic Times.” Critical Trauma Studies: Understanding Violence, Conflict, and Memory

in Everyday Life, edited by Monica J. Casper and Eric Wertheimer, New York

and London, New York UP, p. 20.

ibid., p.25.

Schwab, Gabriele. Haunting Legacies: Violent Histories and Transgenerational Trauma.

Columbia UP, 2010, P. 3.

ibid., p. 22.

Halbwachs, M. On Collective Memory. Edited and Translated by Lewis Coser, Chicago

UP, 1992, p. 54.

ibid., p. 61

ibid., p. 64.

Biswas, Manoshanta. Banglar Matua Andolon: Somaj Sanskriti Rajniti. Kolkata, Setu

Prakashani, 2016, p. 262.

Haldar, Sudhir Ranjan. Dandakaranyer Dinduli. Chakdah, Kamala Publishers, 2014, p. 7.

ibid., p. 8.

Biswas, Manoshanta. Banglar Matua Amdolon: Somaj Sanskriti Rajniti. Kolkata, Setu

Prakashani, 2016, pp. 265-66.

Haldar, Sudhir Ranjan. Dandakaranyer Dinduli. Chakdah, Kamala Publishers, 2014, p. 30.

ibid., pp. 32-33.

ibid., p. 42.

Rodrigues, Valerian, editor. The Essential Writings of B. R. Abmedkar.

New Delhi, Oxford UP, 2002, p. 263.

Haldar, Sudhir Ranjan. Dandakaranyer Dinduli. Chakdah, Kamala Publishers, 2014, pp.

133-34.

ibid., p. 134.

ibid., pp. 134-35.

ibid., p. 135.